slow is smooth and smooth is fast

Moontower #294

Friends,

I really hope to be helpful today so bear with me as this isn’t the rosiest way to begin.

This tweet halted my scroll:

For whatever reason, AOL (what year is this?) has an unpaywalled copy of the article:

It’s short, but let me pull an excerpt anyway:

For the past several years, America has been using its young people as lab rats in a sweeping, if not exactly thought-out, education experiment. Schools across the country have been lowering standards and removing penalties for failure. The results are coming into focus.

Five years ago, about 30 incoming freshmen at UC San Diego arrived with math skills below high-school level. Now, according to a recent report from UC San Diego faculty and administrators, that number is more than 900—and most of those students don’t fully meet middle-school math standards. Many students struggle with fractions and simple algebra problems. Last year, the university, which admits fewer than 30 percent of undergraduate applicants, launched a remedial-math course that focuses entirely on concepts taught in elementary and middle school. (According to the report, more than 60 percent of students who took the previous version of the course couldn’t divide a fraction by two.) One of the course’s tutors noted that students faced more issues with “logical thinking” than with math facts per se. They didn’t know how to begin solving word problems.

The university’s problems are extreme, but they are not unique.

The article drones on. None of it uplifting.

“We call it quantitative literacy, just knowing which fraction is larger or smaller, that the slope is positive when it is going up,” Janine Wilson, the chair of the undergraduate economics program at UC Davis, told me. “Things like that are just kind of in our bones when we are college ready. We are just seeing many folks without that capability.”

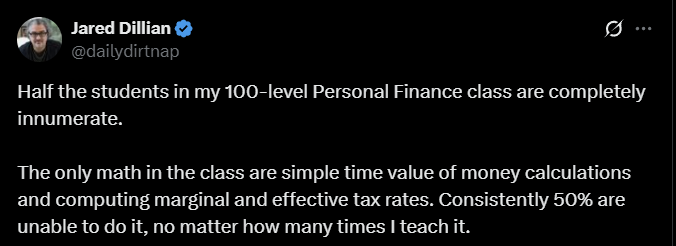

Here’s Jared’s firsthand experience as a teacher while quoting that article:

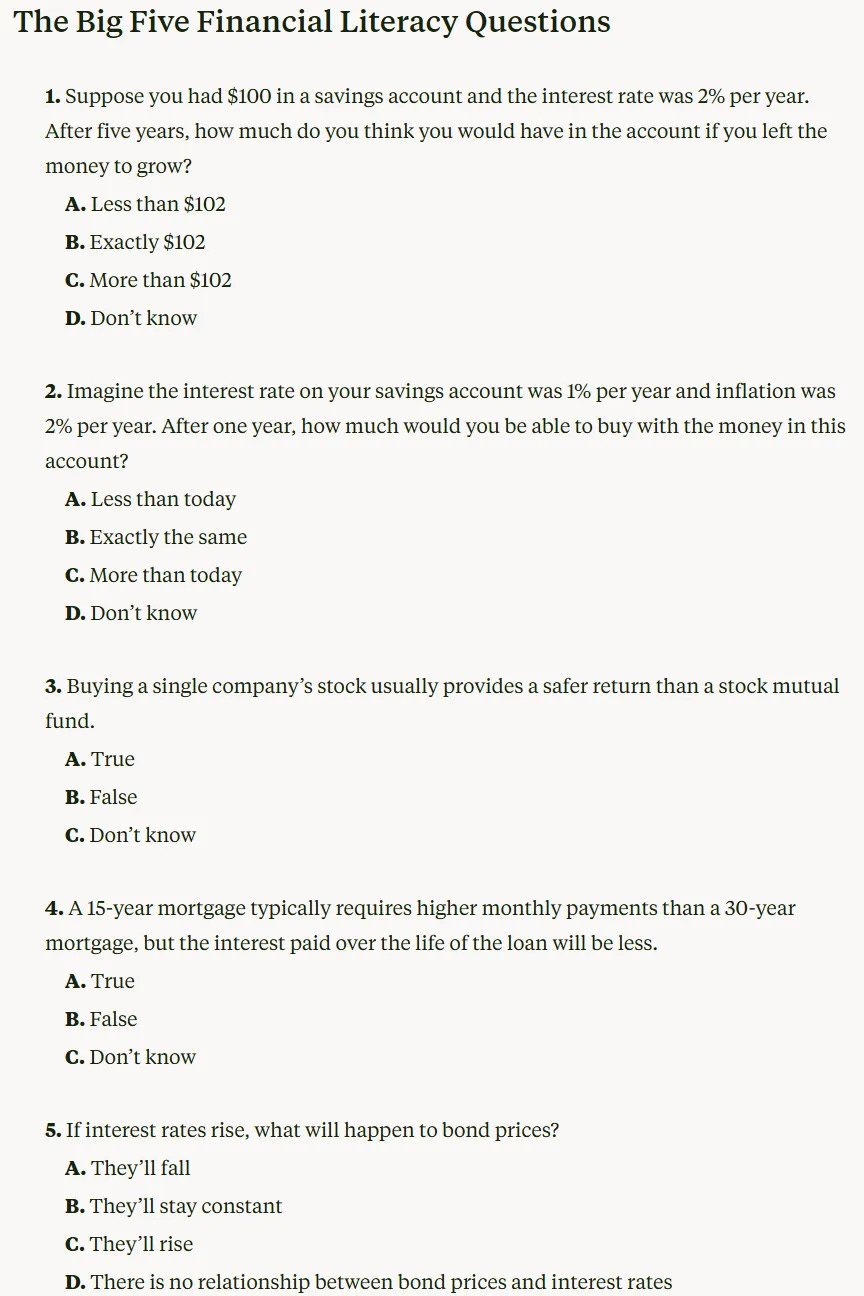

This should remind you of this quiz from 2 weeks ago…

Victor Haghani referring to the quiz (emphasis mine):

It is well-known (and disturbing) that the financial literacy of this audience is, on average, quite low – as evidenced by a mean score of 56% (yes, that would be an “F” if not graded on a curve) on the below five-question quiz, known as the “Big Five” test by researchers. A survey conducted in 2021 found that less than one third of respondents answered at least four of them correctly, the threshold researchers define as “high financial literacy.” At least as concerning as the low test scores is the fact that the scores themselves have fallen dramatically between 2009 and 2021.

Are you seeing a pattern?

The useless question is “why” all this decline. Is it the phones, social media, microplastics, fluoride, the mentality that “kindergarten is the first step to Harvard” is less about upholding standards and more about suing teachers who give bad grades (just scroll thru the results)?

Probably all of them, I don’t know.

And then you have this response to Jared from our mutual friend:

The public discourse amplified by the rich and powerful is tuned to spread to the lowest common denominator. So the average person notices that rich people sound stupid and mistakes the mask for the face. The spread of information has also made corruption more obvious. That Trump’s favors are openly for sale is celebrated by his defenders as transparency. “They were all doing this, at least now we can see it”.

Fine.

I’ll let you keep that defense, but it’s hard to hear that without also hearing “we should all be allowed to crime”. Populism brings some unintentional equilibria I suppose. [I’m warming up to the idea of paying all politicians a salary of $2mm/year but making them truly public servants. All your financial affairs on full display. The fact that Congress can insider trade tells me we are so far from accountability with teeth.]

Adam’s observation is an instance of the current hypernym: honesty is for suckers.

Don’t get me wrong. This is a permissible instinct as trust in institutions disintegrates. But we risk some baby/bathwater mistakes if we malign all institutional failure as rot from within (university-industrial complex) rather than the natural difficulty of keeping up with accelerating times (securities regulation). Human affairs, the realm of politics and coordination, don’t move as fast the electrons re-shaping power and that impedance mismatch is a source of static. But that’s not nefarious. It’s just social physics.

That was a long digression to land me back where I was headed anyway — “be dumber” is an overfit to a moment we are all struggling to understand. It’s a retreat from responsibility. A cop-out. Hopium that there’s a quick way to get above this fray, shielded from the stray bullet from any of cultural ails lurking below the seemingly healthy SPX price.

I’m sorry but you can’t fake A yourself to flourishing. The flourishing is a by-product of the wax-on, wax-off. Confidence in your competence. Having some real to offer. There’s no “getting through this moment” because life is just one of these moments after another. So tie yourself to the mast of self-efficacy and it will all feel calmer.

If you tell me we’ve gained something from the loss of standards above, I’ll listen. But what hasn’t changed is you need something to offer. Society is not your parents. It doesn’t love you unconditionally. It’s hard to make beneficial choices if basic literacy and numeracy isn’t automatic. “I’ll just ask the LLM”. Well, knowing how to ask good questions itself takes intelligence and learning.

[Personal conviction…I think the quality of someone’s questions is a strong indicator of their thinking skills. This is pretty obvious if you spend too much time on X, but a universal example is to think about the last time a child asked you a question that had you go, “Damn, smart kid”. A know-it-all like the nasal boy in Polar Express comes off as obsessive, maybe smart, definitely annoying (although not a crime). But asking the right question reveals layers. For the finance heads, it’s why Jane Street uses this prompt in interviews — see thread. To just give an answer is to misunderstand the exercise.]

Ok, so the trends in reading and math say we are less and less prepared to engage in sophisticated reasoning. And we acknowledge that reasoning is important because it’s the basis of decisions and decisions are the bridge between our internal selves and our physical experiences and conditions.

How do we reverse the trends?

I don’t have an answer for society but I do have answers for you. And your family. And your friends. (“Hey, doesn’t that scale up to society?” That’s cute, did you just arrive from Mars?)

The answer has 2 facets and since we started in the context of math we will stick with it, but I don’t think it’s limited at all to math.

1) The belief that the process of learning itself makes you smarter

We all have potential. Just like in sports. You can’t be Usain Bolt but you can always get closer to your ceiling. We choose which domains to try to move closer to our ceilings since we can’t work on everything. We prioritize based on goals. Fitness, chess, cooking.

Math and literacy touch everything, whether you want them to or not. We are all touched by deals, contracts, transactions, even if we just want to paint. Youth is the rare stage of life where there is time carved out specifically for upskilling your general-purpose machinery of abstract thought, the manipulation of symbols, and the ability to maintain a chain of ideas inside one brain. I’m not sure if the appeal of doing so is universal, but the fact that games and puzzles are not compulsory and in fact pulled, not pushed, suggests that there is something intrinsic about cognitive self-improvement. Fostering this urge requires no justification beyond “it’s fun” but it happens to have salutory effects across your mental wetware and let’s face it, your job prospects, if you insist on being purely practical.

So this gift of time that children are afforded is when the skill of skill acquisition should be taught. I emphasize this because school is treated not as a place where we acquire skills but a place to trot them out for approval. The difference is insidious. As you traverse the years, it’s not what did you master, it’s what grade did you get? There’s really no emphasis on mastery. It’s just “did you go through the motions” for most, and then for the top students, who may or may not have achieved any type of mastery (and if they did it wasn’t to the school’s credit), the school is just a sorting hat. And with grade inflation a bad one at that, making students (and their parents) feel like college admissions is plinko.

My HS diploma-only mother emphasized school because education was the path to a better life. But she specifically stressed math because she thought it literally made you smarter. Her opinion is backed by nothing but intuition and self-flattery (she was a strong math student). But Ced, whose practice and writing is maniacally obsessed with the art and science of getting good at things and separating b.s. that sounds like it works from what actually works in complex domains, sent me a link to mathematician David Bessis’ interview with Russ Roberts:

🎙️A mind-blowing way of looking at math (Econtalker)

Bessis echoes what my little immigrant mom said. In describing what we need to do differently in teaching math, he argues we must not mince words to motivate:

I think teachers should be bold. They should say, ‘It makes you smarter.’”

More:

People hate math because they view it as an IQ test that they’re failing. And, it’s not a test. It’s a technique to get smarter.

If you’re failing, it’s normal because you start. When you start any new sport, you suck at it. There’s no way you’re going to be good on Day One. Just because a two-year-old is babbling, you don’t say: Well, I guess he’ll never learn to speak, but we just won’t bother teaching him language because he’s not good at it. And yet, we do that with math. We say, ‘Well, he’s not a math person. He’s not good at math.’

You cannot teach mathematics to kids who are convinced that your mathematical ability is something that is static... A combination of confusion about the nature of mathematics, and confusion about how the brain operates, and confusion about the origin of the shocking gap of abilities that are visible on a given day in a given high school makes us believe that this thing is entrenched and you’re not going to be able to change it. But it’s not true.

The failure of teaching mathematics—and it’s something that has been going on for not just centuries, but actually millennia—is the failure to admit that we do things in our head. We play with our intuition, we play with images, and these things have traditionally not even been discussed as being part of mathematics.

At school, you enter the room with your intuition, and the teacher is telling you that your intuition is wrong; and you reach your conclusion that intuition is bad and that you’re stupid. But, the thing is, it’s wrong, but it’s not going to be wrong forever. You will gradually evolve your intuition if you confront it with this very special apparatus that is logical formalism.

Mathematics is a technique that, if you learn how to master the technique itself, you will develop your intelligence; you will utilize your brain in a way that you would not be able to otherwise.

But this is really cutting to the heart of my mother’s hunch, which she couldn’t articulate:

I knew when I was a mathematician that what was really interesting to me was not the mathematics: it’s that kind of meta-cognition that you have to learn to become a mathematician. And this is the topic of the book. What do you do inside your head when you become better at mathematics?

It’s worth mentioning that much of the interview is spent on intuition and what Bessis, playing on Kahneman, calls System 3 thinking:

Whenever you catch your intuition red-handed being wrong at something, don’t throw that away. Don’t reject the intuition... Explore it. Try to unpack it... do back and forth until they agree. It may take you five minutes, one hour, a day, a week, a year, 10 years, 50 years.

Bessis argues that this process of confronting incorrect intuition is a uniquely valuable habit because it creates a highly memorable learning stimulus. This rings so true personally. When something goes wrong, when you are snapped out of autopilot, or surprised, the lesson you learn sticks with you.

His last inversion, namely, that math is not a test of smartness but it makes you smarter is a hokey story of being intimidated when Bessis noticed legendary mathematician Jean-Pierre Serre in the audience. After the Bessis talk, Serre said he’d need to repeat the talk because he “didn’t understand a word of it”. Serre was being sincere. Bessis noticed that most people would not admit to incomprehension so easily. And while it’s much easier to do so if you are Serre, whose capabilities are beyond reproach, Bessis wondered:

“Maybe with that attitude, you can become Jean-Pierre Serre.”

Ok, so the first step to improving our abilities in math (or literacy) is believing it’s possible and worthwhile.

The next step is to know how to actually acquire the skills.

2) Skill development is not the same as education

School is time-based education. You do X in 4th grade, Y in 5th and so forth. There’s some acceleration but it doesn’t stretch as far as individual variation because the range would be too wide to contain in a single classroom. The compression hurts not only the top performers but the bottom performers who are hanging on for dear life only to be waved through to the next grade, where the deficiencies compound.

Skill development is rooted in learning science. You are far more likely to have encountered its prescriptions in sports or music than school. I encapsulate a lot of that information in The Principles of Learning Fast. But today I want to zoom in specifically on our foundations because it’s an actionable target if you are insecure about your knowledge and how to go about learning to mastery since you may have never realized that was an option. How could you have realized that…there’s a test tomorrow you need to study for even though you don’t understand the material from last week’s test, right? It’s not your fault but hopefully what you’re about to learn can serve you and your loved ones going forward.

I’m going to let Alpha School’s Joe Leimandt be the messenger. The following flow comes from an interview he did with Patrick O’Shaughnessy.

🎙️Building Alpha School, and The Future of Education (Colossus)

1) Knowledge is hierarchical

Most of knowledge is hierarchical where it’s based on foundation. Algebra is basically advanced fraction manipulation. Fractions is multiplication and division. And you can just keep going down the tree where you have to actually learn bottom-up and have mastery.

2) Well, what is mastery?

Think of a sports analogy like in basketball. If you’re the point guard and you lose the ball 30% of the time going down the court, the coach is not going to be like, hey, let’s work on the alley-oop. They’re going to be like, okay, let’s get back to the basics and master the basics so you can get down the court.

Have you mastered the basics? How good are you? We always talk about in standard school, there’s a whole set of things that 70%—you’re passing, you don’t know 30% of the material, and then they move you on to more advanced things.

This is pretty obvious stuff. You know how this feels:

3)The Swiss Cheese Problem

The problem’s not the algebra, it’s the prior knowledge... if you’re pushing people up and they’ve only learned 70 or 80% of the curriculum, you should think it’s like Swiss cheese. It’s like you’re building a foundation with all these holes. And then eventually as you get high enough, it just gets too much and it collapses and you can’t learn anymore.

4) Going Back to 3rd Grade

If you’re doing fractions and you haven’t mastered division, you’re going to sit there and say, God, this fraction problem is really hard. But the real issue is, well, just go back and learn your division and then the fraction’s going to be easier.

We have one student who was, this is sort of a unique, an extreme example and I hesitate to say it but we had a student who was 740 on the math SAT and in looking they were making careless errors. Some of the problems they were overloading working memory and for whatever reason the student didn’t have fluency of multiplication and division tables. So we literally sent her back to third grade math.

We’re the only school in the world who will take a 740 math SAT student go back to third grade, send back and she got a 790, a 790. And it’s that kind of thing where when you talk about the science of learning and just I say it this way, the parent and the student in this case were not excited that their 740 math student is being given third grade problems. That can’t be the issue, but it is. It is, because you’re overloading the working memory and she’s just making careless mistakes.

My eldest is 12. I keep telling him that the form on his basketball shot is off. He finally asked me to show him a video of him shooting. After seeing it, HE decided he wanted to correct it. He understands it’s a step back to go forward. I gave him tremendous praise for the decision because it’s not easy to make choices like that. It’s an investment in the bigger picture

[He’d like be able to make the HS team and it’s gonna be competitive. His current shot won’t cut it, especially since I don’t expect he’ll be very tall.]

My wife is going to start Math Academy because she sees the kids’ work and, well, there’s lots of swiss cheese in her knowledge. She decided that didn’t sit well with her. The kids asked her what level of math she’s gonna rebuild from and while the diagnosttic will place her, she has no shame about however far it suggests. The 12-year-old would bet he’s ahead and she’s not taking the other side of that.

Everyone is anxious about time. Finish so you can get to the next thing and the next thing. I’m very sympathetic. Things just feel like a race. Business is often a race. It’s hard to backfill expertise or keep up with all the cool new stuff when you’re putting out fires. So I don’t know to what extent we as adults can choose mastery for ourselves. I don’t pretend to know your constraints. But when it comes to the kids, I urge you to think about this stuff. You know what it’s like to have swiss-cheese in your foundation. Holes are not totally avoidable. But rushing to check off “done” is training for a life of cramming. Of seeing a stimulus to grow as an obstacle to relaxation rather than an opportunity to expand your capacity to offer something to others.

That’s a real goal. Not a fake one. Getting there takes as long as it takes for you. But once you’re there you can’t be shaken because the foundation is rock solid. The title of today’s letter is hook to remind you:

Slow is smooth, and smooth is fast

There’s no shortcut to smooth.

Money Angle

A friend was asking me how to deal with a loved one who had put nearly all of his assets into a particular volatile stock and done very well. So far. The person is in their 30s with a family and my friend is concerned that if things go the other way this could be the type of thing the household might not recover from.

I asked the basic questions which of course my friend also asked. What’s your plan if the stock falls? “Probably buy more”.

Do you have a target where you’d be willing to sell any of the shares? “If it doubles again, I can retire so nothing before then.”

We can sit here and talk about risk management and yadda yadda. But I’m gonna share something personal which makes me think this has nothing to do with rational finance thought.

I’m close with people that have been taken in by pretty obvious scams. All the red flags. But the people I know are smart people. People that can compute an interest rate and all. They don’t tell me about the “great opportunity” because they know I’ll plead with them to not do it.

Predictably, they get burned. (I’m not supposed to know that because they don’t want to hear I told you so. But I know.)

They fall for this because they want to believe so badly that their better judgement doesn’t stand a chance. I’m totally nonplussed by this. It’s fascinating that we are capable of this. It explains quite a lot, good and bad, actually. But it’s not suprising if you pay attention.

But here’s the part that I found surprising and discovered on a lark.

In the aftermath of the scam, I spent 2 hours on the phone with a victim. I was standing in my kitchen of the last house. Beautiful day outside. Brutal conversation. Emotional. Just trying to make sense of it in a way where we could at least salvage some vague sense of growth out of the closure. At the tail end of our call, I asked a question that I still find peculiar but somehow felt appropriate:

“Did you need to lose that money?”

Silence.

I could hear them think.

“Maybe”.

We talked about it. There was nothing that could have been done. No warning I could have given would have talked them out of it. They admit to that.

I think about this a lot.

I told my friend whose concerned about their loved one this story. And the friend’s face dropped. They know what they’re up against.

(We actually came up with 2 proposals that he could bring to the loved one to change the shape of this death wish, we’ll see if either find reception.)

Anyway, as BTC has been dropping, this thread has been on my mind because there are a lot of cult leaders who benefit from persuasion but aren’t accountable to their followers’ families if they’re wrong.

I’ll just leave you with a tweet I sent Tuesday:

Sitting down at a table without a budget is a commitment to playing til you’re wiped out.

Stay groovy

☮️

Moontower Weekly Recap

Posts:

Need help analyzing a business, investment or career decision?

Book a call with me.

It's $500 for 60 minutes. Let's work through your problem together. If you're not satisfied, you get a refund.

Let me know what you want to discuss and I’ll give you a straight answer on whether I can be helpful before we chat.

I started doing these in early 2022 by accident via inbound inquiries from readers. So I hung out a shingle through the Substack Meetings beta. You can see how I’ve helped others:

Moontower On The Web

📡All Moontower Meta Blog Posts

👤About Me

Specific Moontower Projects

🧀MoontowerMoney

👽MoontowerQuant

🌟Affirmations and North Stars

🧠Moontower Brain-Plug In

Curations

✒️Moontower’s Favorite Posts By Others

🔖Guides To Reading I Enjoyed

🤖Resources to Get More Out of AI

🛋️Investment Blogs I Read

📚Book Ideas for Kids

Fun

🎙️Moontower Music

🍸Moontower Cocktails

🎲Moontower Boardgaming

Great read. Throughout the article I kept thinking about the value of resilience - one can achieve anything they put their mind to with it.

I'm curious what your thoughts are on "naturally" smart people and whether you believe those even exist or if it's just a cycle of confidence leading to better skill acquisition? Thanks again

The power of mathematics is that it's great practice for developing learning representations (and why it's unreasonably effective in physics). Yoshua Bengio's article on Learning Representations is a clear distillation of principles, for children or adults: https://amicusai.substack.com/p/learning-and-leverage