Friends,

For the first Sunday of the New Year I want to boost a brief and useful post for 2024:

Harder Than It Looks (5 min read)

Jared Dillian

A short and sweet line:

I do not react, because I am not an animal.

I did a tweet version imbued with the same spirit almost exactly 2 years ago. Let’s call it Parking Lot Empathy:

Money Angle

I am disappointed with investing section of my last post Plane With Zits. Let’s remediate the problem with it and see where we land.

Recapping:

a) We recalled how volatility, a first order quantity, “drags” down median returns in a non-linear fashion

The volatility term drag is a squared term. This is same intuition can be appreciated from another angle — if you lose X% you need to gain back X/(1-X) which you can plot in your trusty TI-82 to see it’s non-linear.

Lose 10% you need to make 11% to get back to even.

Lose 33%, need to gain 50%.

Lose 50%, need to gain 100%.

Lose 75%, need to gain 300%

b) I showed why the impact of large drawdowns have an outsize impact on CAGR

My toy example assumed compounded returns of 9% for 19 years then 45% drawdown.

c) In such an event you are roughly in the same place had you put 50% in stocks and 50% in bonds yielding 4%

As soon as I hit send I started to feel weird about it. I did something lazy. And the problem got worse because I got 3 messages from people saying it was one of the best things they’ve seen because it confirmed intuition but hadn’t seen it presented this way. But there’s a problem with it. In fact I told one of the readers to call me because I wanted to explain why this needed revision.

So as a mini-test, ask yourself what the problem is? (It’s not a tax thing either).

🤔

Ok, let’s just jump in to the thought process and the fix.

I originally picked 9% because I wanted a CAGR that our collective conscience would agree is a reasonable guess for what long-term equity index CAGR is.

The problem is I can’t use 9% for 19 out of 20 years because the 20 year CAGR needs to be about 9% inclusive of the drawdown! Our perception of what equities return includes all the terrible times already. I can’t just use that CAGR and then bolt on 45% drawdown.

Instead, I needed to:

Pick a number for those 19 years that was higher than the CAGR

Apply the 45% drawdown

Make sure the resulting 20 year CAGR was 9%

Once I got to that point I just looked up what SP500 monthly returns were going back to 1926 via https://www.officialdata.org/us/stocks/s-p-500/1900 (The SP500 index didn’t exist then but since they base this on Robert Shiller’s work I’ll just assume the historical reconstitution is valid).

Using monthlies, the data set includes 1161 rolling 12-month returns. We find:

Annual Simple (arithmetic) Return 11.4%

Annual CAGR: 10.2%

Annualized volatility: 15.4%

.50% (ie 1 in 200) of these returns include a 12-month loss of 45% or greater

In the last post I made the disaster year occur 1 out of 20, but historically the odds were much small than that measured at monthly resolution.

I re-did the computation assuming that the typical year is an 11.4% return and allowed 2 variables to vary:

the disaster year return (R)

the probability of a disaster (p)

The formula in each cell is:

The table output:

(emphasis on cells with a roughly a 10.2% CAGR)

This is not a stock simulation so the 11.4% assumed return can just be thought of as a compounded return net of the volatility. This isolates the effect of a 12-month drawdown of R for probability p just to see how sensitive the total CAGR is.

It’s not until a 45% disaster occurs in 1 in 50 to 1 in 200 years does it threaten to knock a full 1% off the CAGR.

This might make readers now rush to the other side of the boat…”hey it’s a great idea to put 100% in stocks”

But remember, the history of the US stock market is a small sample size. The true sample size requires looking at non-overlapping returns as opposed to rolling 12-month returns. Which means you get as many data points as you do years.

Plus it’s only the US.

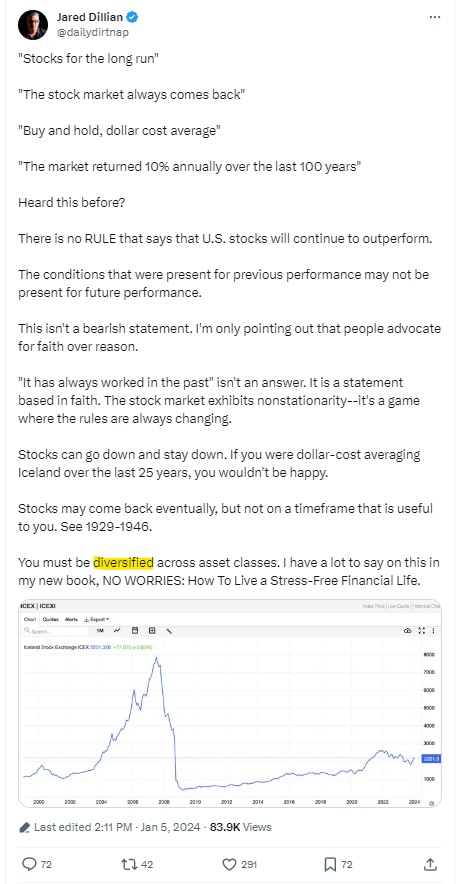

Jared appears again (I’ve been reading him for a decade…his personal finance book comes out soon and this tweet is timely for this post):

But let me add a mathematical point to the discussion…looking at monthly returns hides the emotional path as well as knowledge of the distribution.

Let me explain. Standard deviations are normalized measures. They are move sizes scaled to time.

The Socratic demonstration:

Is it more likely for a stock index to fall 10% in 1 year or 1 day?

That’s easy, in 1 year of course. But the return by itself is not normalized for time. It’s just a raw number…10%

Let’s ask this another way.

Is it more likely for the stock market to fall 3 standard deviations in 1 day or in 1 year?

You should now choose 1 day.

Think of it this way…in 1987 the stock market fell more than 20% in one day. I don’t know what SP500 volatility was leading up to the crash but I’d be surprised if the daily standard deviation was more than say 3%. That day would have been 7 standard deviations.

You have never seen a 1 year 7 standard deviation move.

Largest single day moves for the Dow:

Using the overlapping data from earlier we find 3 annual standard deviation moves occurring .50% of the time (fatter than normal distribution) but some of these daily moves would be considered impossible.

The shorter the sampling period, the fatter the tails.

Or said otherwise:

For a shorter time horizon, the 1% probability move will be more standard deviations than the longer time horizon. (You can see this implied in option surfaces as well)

So if you look at returns at low resolution, you miss the experience. Even if you look at 2020 monthlies, it doesn’t seem anywhere near as significant as the feelings you had as an investor through it.

Summing up:

Using monthly and annual resolution, I overstated the risk.

But risk depends on the resolution. If you are an investor and can avoid looking at your account, you actually witness less volatility (on a standard deviation basis)! This is an argument for ignoring path.

The problem is there’s nothing about past US returns that indicate what the future holds. Assuming real returns (after-inflation) of 6% is aggressive.

100% stocks when your investing life is one draw from a 40-year series has more to do with faith than judgement.

From My Actual Life

A few things I’ve been enjoying during the break.

The morning puzzle routine with the kids. We do the suite of NY Times games: Wordle/Letterboxed/Connections/Mini as well as the Set Daily Challenge

We have been playing the Mafia (sometimes called Werewolf) social deduction game. There’s nothing to buy and I spiced it up with some GPT-enabled storytelling weaving in elements from real life. I wrote it up here:

Mafia: The Social Deduction Party GameA friend I met through my wife’s work is a musician and has my tastes totally dialed in. He turned me on to King Gizzard and The Lizard Wizard, Khruangbin, and he just struck again — he sent me Natural Child’s Be M’Guest record which I’ve been playing non-stop. From AllMusic:

Natural Child are a trio whose good and greasy style is informed by Southern rock, vintage country-rock, laid-back Laurel Canyon sounds, '70s-style boogie, a dash of hard rock, and most likely a careful balance of liquor and bong hits

Finally for New Year’s Eve we had a chill night with the in-laws but decided to spice it up by trying something new…a Murder Mystery Dinner.

Here’s my guide:

I Hosted A Murder Mystery Game For New Year’s Eve

This is me as a pompous avant-garde movie director throwing a party in the Hollywood Hills to celebrate the the completion of the filming. With me is “Patty Field”, the costume designer who’s motive was fatal attraction apparently.

Stay groovy ☮️

Moontower On The Web

📡All Moontower Meta Blog Posts

Specific Moontower Projects

🧀MoontowerMoney

👽MoontowerQuant

🌟Affirmations and North Stars

🧠Moontower Brain-Plug In

Curations

✒️Moontower’s Favorite Posts By Others

🔖Guides To Reading I Enjoyed

🛋️Investment Blogs I Read

📚Book Ideas for Kids

Fun

🎙️Moontower Music

🍸Moontower Cocktails

🎲Moontower Boardgaming

Ways To Support Moontower

"Risk depends on the resolution". Great Comment. I invest in real estate LPs. They run 3-6 years and have no intermediate liquidity, and thus no perceived volatility. I review the financials, and operating reports, but there is no mark to market.

On the other extreme 3x leveraged ETFs like TQQQ can have tremendously bad days, which you don't see looking at monthly numbers.

I enjoyed your explanation summary, too: "The shorter the sampling period, the fatter the tails."

The difference in the emotional experience between trading 3x Leverage daily and (roughly 3x Real estate using 25% equity) RE LPs is starkly different.

Yup. I was telling a friend this the other day - if you're going to put money in the stock market, you have to plan on holding for at least 10 years because if you randomly draw from a 10 year return distribution, you are very likely to harvest a great return; whereas if you randomly draw from a 1 year return distribution it isn't clear at all that things will go well.

Also, global diversification to avoid taking a country-centric bet. So $VT>$VOO. And some degree of asset class diversification to avoid an equity-centric bet. So VT + TLT (efficient frontier max sharpe) > VT alone.

And if you calculate kelly bet on historical equity returns, you'll realize 100% equities is already > 1/2 kelly. So If you reduce the volatility by diversifying into bonds you don't need to lever up to get the sharpe, you can just sit tight as the diversification moved you to a more tolerable kelly fraction.