Friends,

Real estate people understand the value of accounting losses in service of deferring taxes while an asset’s returns compound.

In the institutional investing world many investors such as endowments are tax-exempt.

Retail investors in public stocks have less places to hide outside of tax-advantaged accounts which are hard to jam lots of assets into in the first place.

The rise of ETFs have come with some relief on the tax side as you decide when to pay taxes because you decide when to sell even as the holdings are rebalanced. Mutual funds can leave you footing a prorated portion of the pool’s taxes regardless of how long you’ve been an investor.

While the ETF advantage is real it’s relatively minor compared to the ability to tax-loss harvest. By owning the individual components of a stock index you can sell losers, rebalance into peer stocks, and accumulate short-term losses to offset long-term capital gains on the subset of names that moon.

I say minor because of the “brain damage” (more effort, slippage, tracking error although if it’s random only matters if you’re managing money for others) and higher management fees associated with TLH. See Alpha Architect’s The Costs and Benefits of Tax-Loss-Harvesting (TLH) Versus an ETF.

Another restraint on TLH enthusiasm is limitation on writing off losses greater than $3,000 per year. Losses are more valuable in an NPV sense if you can use them to offset significant capital gains when diversifying out of a large gain in a concentrated position. With markets where they are, especially the Mag 7 and BTC, this is common high-class problem.

Still, the fintech world with the rise of robo-advisors and software is enabling both retail and advisors to “direct index” making TLH both easier and less costly.

Getting a sense of proportion

Let’s do some simplistic hand-wavey math to get a sense of proportion for how TLH might work if you were simply long a $1mm basket of stocks.

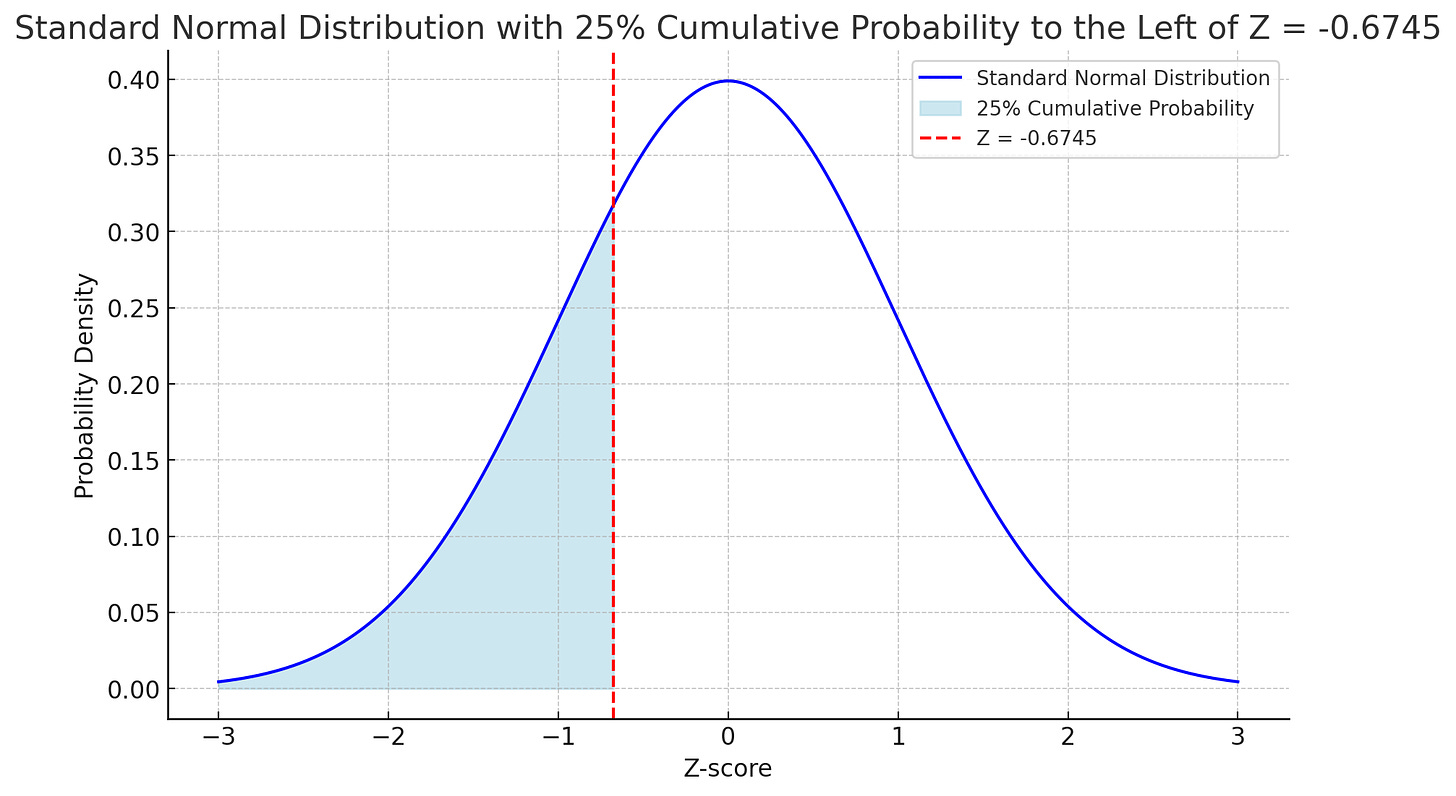

Assuming individual stocks were i.i.d. (“independent and identically distributed”) with expected mean monthly return of 0 and standard deviation of 10% (10% *√12 ~ 35% annual estimate of single stock volatility) then conditional on a stock being down its expected loss is 6.75%

This is symmetrical. Given that a stock is up the average expected return is +6.75%. We are just using arithmetic returns.

In mathematical expectation you expect the portfolio p/l to be 0, with half the stocks up and half down. Thinking about the portfolio as 2 halves, you expect $500k to earn 6.75% or $33,750 and $500k to lose $33,750.

Now suppose you rebalance the losers into a Wario basket of names that have the same exact characteristics as the ones we sold. You have now crystallized $33,750 of short-term tax losses but our exposure is the same. You have gained an asset to offset future tax liabilities.

Just staying simplistic, if all the stocks proceed to go up by 5% over the next 365 days and you sell on day 366 to get LTCG treatment (assume 23.8% — which is just Federal!) then what is your after tax return?

Winning stocks:

$533,750 * 1.05 = $559,728.75 or $59,728.75 total profit on a basis of $500k

Losing Stocks:

$466,250 * 1.05 = $489,562.50 or $23,312.50 profit on a basis of $466,250

resulting in:

+$83,041.25 LTCG (5% on $1mm exposure)

-$33,750 short term losses

= taxable gain of $49,291.25

tax bill = 23.8% x $49,291.25 = $11,731.32

After cutting the check what do you have in your account?

$1,049,291.25 - $11,731.32 = $1,037,559.93 or a 3.75% after-tax return.

💡The tax benefit

You’ll notice that if you bought $1mm of an ETF that went up 5% in a year and sold on day 366 your $50,000 profit less 23.8% taxes would net you about the same after-tax return.

So where’s the benefit?

It’s in the optionality of this pool of short term losses that you have control over. You could just let this $1,050,000 portfolio grow and keep the short-term losses as an asset in your back pocket to use against future tax liabilities, some of which are going to be taxed higher than LTCG rate. Alternatively if you need to divest a large chunk of a profitable position to raise cash, you’ll have a large pool of losses to offset the gain.

The real value of TLH emerges when:

Offsetting Higher Tax-Rate Gains

Short-term capital gains (STCG) or ordinary income are taxed at higher rates than LTCG. If your harvested losses offset STCG or ordinary income, you reduce your taxes significantly.

Perpetual Deferral

Step-Up in Basis

If you hold the portfolio until death, the heirs may receive a step-up in basis, erasing deferred taxes entirely.

Charitable Contributions:

Gains on low-basis positions can be avoided by donating appreciated securities to charity.

This toy example is compelling enough to realize it’s important. But there’s also another flavor of TLH on the scene with the potential to generate significant short-term accounting losses while the overall value of the portfolio grows.

TLH on levered long-short portfolios held in a separately managed account (SMA)

Using portfolio margin and a quant framework (this can range fairly basic to factor-intensive), an investor can run the same beta they desired in a typical long-only ETF but generate significant short-term losses by using their stocks as collateral to overlay a long-short portfolio.

This is typically done with an advisor who will in turn be using a sub-advisor whose infrastructure allows them to scale portfolio adjustments across thousands of custom custom portfolios held in SMAs.

I’ve heard some claims of how much more impactful this can be but again it’s critical to sanity check with actual numbers to make sure the sense of proportion is reasonable. From there you start layering common caveats which are easier to handicap in terms of bps per year.

In this case, the sanity checks called for simulation.

A little foreshadowing — if you are in a high tax bracket or trying to work out of a concentrated position with a low cost basis you are going to want to see this.

You get the simulation code, you can run it in your browser and it will even download the full output. I’ll show you a few manipulations for the output so you can get a strong grasp on the mechanics. This is one of those concepts that you can’t unsee once you see it. Multiple bulbs going on at the same time.

(It’s also quite depressing so much time is spent on taxes and the ROI on that time is validated by the math. Both taxes and the time spent on their minimization is deadweight loss. I like markets, I hate structuring and law and tax and basically all the crap that’s probably higher yield to understand. And just going through this exercise depressed me even further because it confirmed how important it is.)

Onwards…