Primer #3: The Nature Of Edge

Primer #3

As promised, moontower.ai includes a primer which is being dripped 1 post a week right here on substack.

Sign up to get early access here.

In business, it's margin.

Quants call it risk premia.

Gamblers call it edge or vig.

Whatever you call it, without an advantage, there’s no long-term return.

Understanding Edge

Imagine a coin flip game. Heads you make a dollar, tails you owe zero.

That game is worth $.50. That’s the fair value.

How much are you willing to pay to play the game?

If you can buy the chance to play that game for $.40 you are making a 25% margin. Of course, on any single trial, you can lose 100% but if you size your bets appropriately you can survive to realize that 25% margin in the long run.

This is the single big idea behind trading. It is the basis of the entire business. If you can net a 1% edge, you are a casino. With enough chances, you are guaranteed to get rich. Likewise, if you have a negative 1% edge you are guaranteed to go broke.

Professional trading is about identifying, pricing, and accessing these so-called coins or games. That's how you grow the top line. But edge needs to be compared with risk since the sustainability of the business relies on keeping the edge you booked.

To keep things simple, we will just use standard deviation as a proxy for risk. The ratio of edge to standard deviation is similar to a Sharpe ratio. If you have a 1% edge on a coin flip (ie you are buying 50-cent coins for 49.5 cents) then you need nearly 7000 trials to be 95% sure you are profitable. That's over 25 trades a day for a year.

What if you had a 5% edge? With only 1 trade per day, you'd be 95% sure you are profitable. Small edges are pure gold if you get enough chances.

Let’s talk about fair value

In the realm of games and casinos, there are well-defined expectancies or fair values. The fair value of rolling a pair of dice is a ‘7’. We can think of this as a “hard” fair value.

When it comes to investing, fair value doesn’t announce itself at the end of a chain of computations. But investors and traders must still have a concept of what an asset is “worth”.

A popular example of this comes from the world of value investing. Warren Buffet speaks of ascertaining “intrinsic value” — the sum of discounted cash flows that you expect a business to yield over its life. This is a bottom-up approach that relies on deep research, forecasts, and assumptions. It is also the first lens investors are given in their investor education. It makes intuitive sense. “Buy stocks trading below intrinsic value, then wait for the cash flows or wait for everyone else to see what I’m seeing and push the price up to my fair value.”

The novice investor often finds that “intrinsic value”, despite intuitive appeal, has 2 significant obstacles:

1) GIGO — Garbage in, Garbage out

There are so many assumptions and forecasts needed to populate a DCF that in the hands of the average investor, it’s theater not analysis.

2) It heavily discounts the wisdom of markets.

Where one investor sees a cheap stock another might conclude that the market is simply assigning a lower implied future return on invested capital.

Moontower’s definition of fair value is an inversion of the “intrinsic value” approach. It gives the market prices tremendous respect for knowing more than we do.

Instead, we believe:

Fair value is the consensus-driven price that you can easily buy or sell at.

If a stock is liquidly trading in high volume at $60, that’s fair value. If I could buy the stock privately for $59 I don’t care what “intrinsic value” is — I know I can offload it for $60 on an exchange. If Vegas has the Chiefs as a 7-point favorite against the Jets and an enthusiastic New Yorker is willing to accept just 6 points to take the Jets, I don’t need to know anything about football to know there’s money to be made. The liquid Vegas market, which aggregates all relevant knowledge about the game into a single price, says the Jets deserve 7 points. All I need to do is accept the edge and decide whether I prefer to hedge it or not.

Your mind should be flashing a yellow light right now.

“Wait a minute, you’re just talking about arbitrage — that’s great work if you can get it but I don’t have access to counterparties who don’t bother to check exchanges for liquidity.”

You are absolutely correct. We aren’t pitching a magic arbitrage machine. The main point was that recognizing a good trade needn’t have anything to do with bottoms-up analysis. It’s a matter of finding propositions that disagree with liquid markets.

It's the liquid markets that provide fair value, not the opportunity itself.

You don’t trade SPY for edge. You use it to tell you fair value or simply use it to efficiently to lay off the risk you don’t want.

💡Many people are resistant to assuming this level of humility. It’s hard to accept that their opinions are “dominated” by what’s embedded in liquid prices. And yet billions of dollars have been privately made by firms trading their own money from this perspective.

From arbitrage to risk premia

It’s well understood that gaudy levels of wealth can be erected upon a foundation of tiny edges. It follows that the competition for these slivers is intense. You should not expect to see basic arbitrages lying in plain sight. Still, investors, motivated by changing needs and preferences to take or offload risk, create flow pressures that are rarely perfectly matched at the current price by investors with the opposite needs. The net result of this tussle are price changes. These price changes increase or decrease the risk/reward of assets in relative terms. This is irrefutable — all prices are relative — 1 share per X dollars or 1 dollar per Y hours of work.

Every decision to buy is simultaneously a decision of what not to buy.

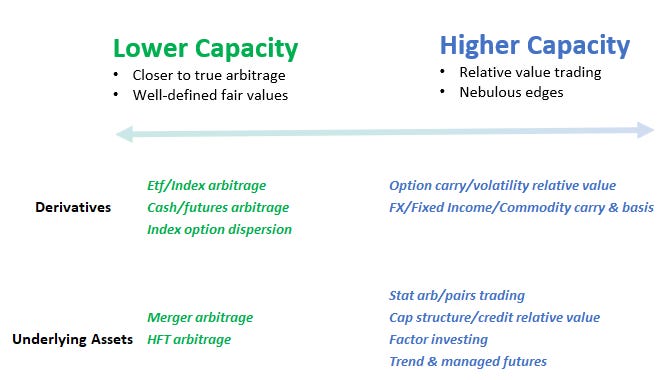

A helpful step in rewiring your investing brain to appreciate the meaning of "fair value" on the continuum of trading edge.

The further you go towards the right, into scalable investing opportunities, the closer you find yourself in the realm of systematic risk premia — low signal sources of investing edge or betas that persist because, while easily accessible, they remain undiversifiable.

The supply chain of edge

The diagram above serves as a handy taxonomy. A snapshot to understand where a strategy lies on the continuum of arbitrage, scalability, and clarity of fair value.

Here's a transaction that happens every day:

First, a wealth advisor in the private client group of a large bank sells a structured note to a family. The note promises zero downside and a portion of the SP500 upside.

The bank then manufactures this payoff with some combination of options. The client doesn’t receive this portfolio of options, just a simple contract explaining the terms. The bank must hold the portfolio themselves to match the cash flows they have promised the client in every possible state of the future. The bank ascertains the cost to purchase this portfolio from the options market, adds a juicy markup, and charges it to the customer. In theory, the customer could simply create the payoff themselves but the bank is in the business of abstracting such a hassle for a fee.

You can envision a supply chain of edge:

The bank bakes in a 50-cent premium per option

The bank spends 5 cents of that margin to “pay the offer” to a market-maker/hedge fund to acquire the portfolio either through the electronic markets or via private “voice” broker deals. The trades can be printed uncompetitively but must still be reported to the public tape.

The market-maker/hedge fund earns 5 cents of edge but must now manage the risk by some mix of delta hedging and relative options trading. If the delta hedging costs them 1/2 cent, perhaps an HFT counterparty to the stock trades is earning half of that slippage or 1/4 cent.

Observe:

The fattest margins are accruing at the point where a non-transparent customer relationship is owned. The smallest margins reside where the trades are most public.

The bank indirectly outsourced the pricing of the options that were the building blocks of the structured note.

The fair value of the options portfolio is a function of consensus — where the marketplace is willing to buy or sell the options, typically at mid-market in liquid names.

The more bespoke a deal is, the less it fits into standardized pricing. That means more edge to whomever provides the liquidity. Banks invest in the apparatus of relationships but of course, are in competition with each other. The battle for edge is forever fractal.

Key Takeaways

1. Outside of pure arbitrage and simple games, the notion of fair value is consensus-driven. Even strategies like “buying below the bid” for the Jets-Chiefs or the structured note examples are ultimately arbitrages by buying below consensus, not some actuarial fair value like the expectancy of tossing dice.

2. If you can buy below what something is worth or sell above, in the long run you will make money.

3. The more liquid a market, the more weight we should give its consensus.

References

On edge:

On relative value thinking:

Understanding why humility/deferring to the market is so foundational:

On the wisdom of consensus:

On the business of trading and the supply chain of edge

Great work and timely since I just wrote a piece about edge in CRE lending which echos a lot of what you wrote here.

https://open.substack.com/pub/cedarshillgroup/p/chg-issue-139-finding-edge-in-cre?r=1qscct&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post