Friends,

What is the single quality that makes someone a pro?

I don’t think “if you get paid for X then you are a professional X” cuts it. I mean any conceptual definition of “pro” which fails to include Olympic athletes is missing the spirit of the word.

“Expertise” falls short. “Professional economist” doesn’t exactly inspire confidence that you are in safe, professional hands.

“Effectiveness” is a necessary, but insufficient delimiter. You got rich because you forgot you once accepted BTC for payment doesn’t make you a professional investor.

The most parsimonious definition of pro I keep coming back to:

A person who consistently studies what went wrong, to get better.

A grandmaster reviews why the opponent moved the rook to D4.

The QB watches film to see how they got baited into a pick-6.

The businessperson who takes the earnest Yelp review seriously.

It’s not fun to look backward. Just as we don’t like to hear our own voices or see ourselves on video, reviewing losses is painful or even cringe. And rewinding the wins can be even harder. We want to just believe we nailed it and move on. Finding out we won for the wrong reasons requires deep swigs of self-honesty. But it’s a key part of being a pro. You don’t walk around with the wrong lessons only to have them defeat you when the stakes are higher.

In Money Angle, I talk about post-mortems in investing. But the reason any of this occurred to me this week was Scott Alexander’s recent post, Why Do I Suck? He sets the stage from the perspective of his readers:

“I loved your articles from about 2013 - 2016 so much! Why don’t you write articles like that any more?” Or “Do you feel like you’ve shifted to less ambitious forms of writing with the new Substack? It feels like there was something in your old articles that isn’t there now.”

First of all, has his writing even gone downhill?

He writes:

Most people think my quality is about the same, although the minority who do see a difference mostly lean towards “worse”. Still, a lot of people think I suck.

So Alexander speculates on the reason people might feel this way. I enjoyed watching him point his amazing powers of observation on himself. I don’t know how writers evaluate themselves (I really ought to figure it out tbh) but his self-reflection carried some clues. I’ll share a few of my favorite excerpts from it.

An unfair reason why his quality may have dropped:

You have your whole life to write your first book, and one year to write your second

This is a publishing industry proverb; your first book gets to use all the ideas you developed over the course of a lifetime, and then they expect you to write an equally good book the next year.

I started SSC at age 28. By that time I already had well-developed thoughts on lots of stuff. Over the course of five hundred essays, I explained most of them to you. Now I’m still learning things and refining my thinking. But not always at the rate of two essays per week.

Novelty is hard to sustain as interesting ideas propagate. The contrast is especially stark if you’re own writing helped spread the ideas. I would describe this as “victim of your own success”:

There was a time when “bets are a tax on bullshit” or “words are cluster-structures in thing space” were new and exciting ideas. There was a time when nobody had heard of the replication crisis unless they happened to be reading the medical journals where John Ioannidis was publishing. The rationalist community scooped all this stuff up, broke it down into easily digestible bits, and put it in one place. I happened to be sitting in that place, which meant I had the privilege of transmitting it to many of you.

His popularity benefitted from being a liberal who was early to criticize the extremes of woke ideology. In other words, his pen was being used in divergence to the crowd. With the extremes of idealogy creeping further from the center, it has become popular for liberals to point out the most comical excesses of wokeness. His views are no longer scarce on a topic people love to get riled up about, so he doesn’t feel a need to write about it. It’s not surprising that his early fans might feel let down.

As Mencken said, “it’s not worth an intelligent person’s time to be in the majority, by definition there are already enough people to do that.”

Expressing a majority viewpoint feels like punching down, or like kicking an underdog. I’ll do it if I have to, because you should still defend the truth even when it’s popular, but I don’t enjoy it. So back when it seemed like everyone was an SJW (which apparently was earlier for me than for anyone else!!) my natural inclination was to push back.

While everyone else is freaking out about wokeness, I’m starting to feel like all my friends are anti-woke. Who’s woke anymore? Are there really still woke people? Other than all corporations, every government agency, and all media properties, I mean. Those don’t count. Any real people? I guess I know one or two SJWs. But I also know one or two Catholics. Doesn’t mean they’re not the intellectual equivalent of out-of-place artifacts.

And that means my natural I-hate-saying-whatever-the-majority-says kicks in whenever I’m tempted to criticize wokeness. I could write about something something critical race theory in school. But first of all, Jesse Singal, Freddie de Boer, and Bari Weiss have probably already written things on it and they probably all did a better job than I would. Second of all, probably the electorate has already figured out it’s bad and is planning to vote out everyone involved. Third of all, do I really want to spend my life reminding other unwoke people that dumbing down math classes and using the extra time to force kids into classes where they chant prayers to the Aztec gods instead is actually bad? Don’t get me wrong, it is bad. But Cicero had Catiline, and Lincoln had Stephen Douglas. I’m hardly the equal of either, but I would like to think I’m cool enough to deserve a worthier foil than the Aztec-prayers-in-school crowd, who everyone else also hates.

And finally, this bit was the most interesting, because it points to such an honset concern. Incentives. He acknowledges something anyone with a public presence, even just a social media account, will understand.

Lately I’ve been finding it helpful to think of the brain in terms of tropisms - unconscious structures that organically grow towards a reward signal without any conscious awareness.

This is my explanation for why so many smart intellectuals, upon being thrust into punditry superstardom, lose all their good qualities and turn into partisan hacks (many such cases!) The positive reinforcement provided by tens of thousands of people saying nice things about them whenever they repeat party line becomes impossible to resist, and reshapes their brain into whatever form keeps the retweets coming.

It’s never been bad enough to actually stop me writing, but it does gradually erode off some of the more idiosyncratic features of my writing in favor of blander styles nobody objects to.

Every time a choice is above the waterline of conscious awareness, I try to stick to the unique polarizing things. But ask Freud how high the waterline of conscious awareness is sometime. Even for the best writers, “style” is a giant black box, and below the waterline it’s the tropisms driving the bus.

I found his post to be reflective, and dare I say, appropriately arrogant. You can judge that for yourself though.

✍️ Why Do I Suck? (11 min read)

by Scott Alexander

Money Angle

In trading, pros use post-mortems to study what went wrong.

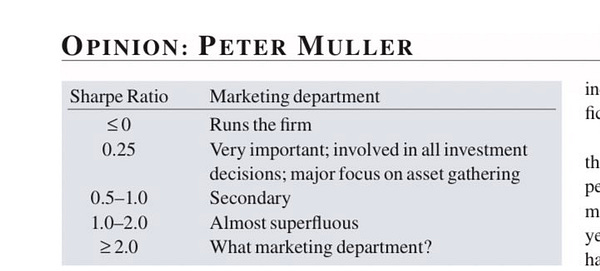

The quantitative is just the starting point. The first step in any evaluation is identifying the correct benchmarks. “Did I make money or not?” is an amateur hour question. A pro doesn’t “result”. (If you suffered a bad poker beat on the river, you would be better off encouraging the winner to keep playing the same way instead of reminding them that completing a gutshot straight on the river in a heads-up hand with even pot odds is a money-incinerating strategy that happened to get lucky.) Properly benchmarked, many investment managers would be revealed to be nothing more than levered beta. Don’t get me wrong, it’s great work if you can get it. But these people are professional marketers. Not true stock pickers.

[One of Matt Levine’s hobby horses is “the primary job of a hedge fund manager is not picking stocks that go up, but rather continuing to manage a hedge fund.” This week he wrote, “If you lose a bunch of investor money one year and the investors don’t take the rest of the money back — due to your personal charm or a reassuring previous history of performance or a compelling turnaround thesis or contractual lockups — then you had a pretty good year.” He was referring to Cathie Wood, but she’s just the example du jour.]

Back to post-mortems.

Quantitative feedback is great at explaining “what happened”. I bought a bunch of vol in XYZ and it worked. But if I had bought SPY vol I would have done better.

But we need to bring qualitative questions to get to the Why?

Perhaps the reason vols increased was not idiosyncratic to XYZ but instead a market-wide stress. The Fed signaled tightening for example. In that case, the driver was a correlation-increasing event so the SPY vol outperformed XYZ. This is the beginning of the harder questions.

Was XYZ actually cheap?

What term was I buying?

What did the term structure look like?

What made the vol I buy screen cheap?

Where was implied correlation at the time?

If my dashboard said it was cheap, what was so special about it that anyone trading with professional size wouldn’t have noticed that too? Which is another way of asking, “who did I trade with”?

To a pro vol trader, vol is vol whether it’s calls or puts. But you need to put yourself in the counterparty’s head. They specifically sold calls which I, through the power of alchemy delta-hedging, transmuted into a straddle and tossed onto my pile of positions without a trace of the original order. In that process, I may have forgotten to think about the intention of the customer’s order.

Was it informed?

If so, was it delta informed or vol informed? Some contras can be both.

Was the result dumb luck? If I’m buying calls, there’s a decent chance it was a benign overwriter.

But why did they pick that time to trade? What’s their pattern? Do they sell on a regular interval, in which case the time chose them?

A professional or firm needs the technical expertise to build the stack required to answer the quantitative questions. But just as important is the uncomfortable process of self-appraisal. Watching film is tedious. Combing through logs of trades is grueling. You are battling entropy, which means the job is never done. The moment you stop, the dust accumulates.

Being a professional doesn’t mean you don’t find post-mortems grueling. Or easy. It means that you understand what is necessary to win, and crucially, you have internalized that winning is more important than the cost. So be careful about what you want to be a professional in. If you find yourself going through the motions of what it takes, you might skate along unnoticed for awhile. But you will still need to answer to yourself. You can’t escape conflict with the truth at some point. If you choose the wrong commitment it will either tear you apart from the outside when you face inevitable failures, or your own dissonance will tear you apart from the inside.

[Random thought: one of my personal hunches about sociopathy is that some people have a robot’s capacity to compartmentalize. This can be adaptively weaponized in our highly financialized, levered world. They tell you it’s raining while they piss down your back. Their logical blindspots are coincidentally self-serving. Maybe these people never get torn apart from the inside. If evolution uses the last few years as a training ground, all the survivors in the next millennia will be built like this if we don’t erase ourselves from the natural world first.]

In an old interview between Mike Lombardi from the Patriots’ front office and Ted Seides, I remember Lombardi emphasizing that greatness came from consistency. Belichick ran a tight ship. You do the same thing every Tuesday. The system isn’t magic. It looks boring.

Only a non-professional would find that surprising.

Last Call

When I was in middle school, I developed a little love affair for vocabulary words. In class, we would learn 20 new words per week. I still remember the author of the workbook’s name: Jerome Shostak.

This was the book they issued. We were supposed to take the entire year to work through it.

I worked through the whole book and its exercises in a few days.

My good friend Kevin did too. He shared my love of words. But the reason we loved words was to be ridiculous. Our goal: stuff as many large words into our homework or tests as we could. Kevin and I would compare notes on how many “vocab” words we were shoehorning into our assignments.

Anyway, my mother saw my interest in this book and bought the entire series for both me and Kevin. We continued our tasteless assault on prose until one day Mrs. [I’m so sad I can’t remember her name right now] pulled us aside to let us know she was on to us.

It was fun while it lasted.

So I ended up with a generous vocabulary by the time I was 11 or 12. But just as kids who Kumon race ahead to be quick at things everyone will know one day, it was a fleeting advantage that wasn’t worth more than saving me SAT prep time. Learning words by reading seems like a more context-hardy strategy but the juvenile desire to flex the “lex” in English class probably did help me retrieve them later (muuuuuch later) when a sense of discretion began to mature.

Fast forward.

According to Wordpress, I’ve published over 600k words in the past 3 years. A lot of my posts are excerpts or overlap with one another so my original writing is likely closer to 100,000 words per year. If I measured in time, I’d estimate 1 hour per day. So in 3 years, that’s a bit over 1,000 hours of writing. And the sum of all this writing is likely more than all the writing I’ve done in my life combined. 10,000 hours feels really far away. And this isn’t the kind of “deliberate practice” that conjures images of Whiplash and a metronome either. I could just be reinforcing mistakes.

It’s not like I’m writing fiction here, but lately, I’ve been wondering what a “writing pro” looks like. Without any formal writing instruction (well besides required freshman year writing seminars which I can’t recall sitting in let alone remember the material or anything I wrote), I have relied on writing tip listicles. You’ve seen them too: write simply, don’t use big words, adverbs are worthless, etc.

The advice always struck me as part true and part suspicious. I have never seen anyone argue against it. Red flag. There must be more nuance. My feeling is that good ornate writing can be even more effective than simple writing, but the bar is higher. But I’ll stop with my own hunches on this and point out a piece that is at least a step closer to the truth than the listicles.

✍️ If Only Simple Were Simple (7 min read)

by Freddie DeBoer

Freddie writes:

“Eighty-seven years ago the founders of America created a country based on freedom and equality. Now that country is going through a civil war, and it’s not clear if a country like that can keep going. We’re standing on one of that war’s battlefields. We’re here to dedicate the field to the people who died here. It’s a good thing to do.”

I think anyone would agree that the first half of the Gettysburg Address is somewhat less memorable this way. The obvious retort is, well, this isn’t Gettysburg, and you’re not Lincoln! And there’s a lot of that sort of thing in the world of writing advice, this constant insistence that whatever you’re writing about, it’s not that important, that whoever you are, you’re not that important, that your writing isn’t that important…. That’s no way to go about having a craft. I don’t know why people have decided that there’s virtue in seeing your work as trivial, in writing, but I’m pretty damn opposed to it. For a lot of reasons, a primary one being that this can be a brutal business, and if you don’t take it seriously then the hard financial times will compel you to quit. That’s one of my foremost pieces of life advice for anyone, actually, to take yourself seriously in a culture full of people trying to build self-defensive shields by trivializing their own lives: take yourself seriously, because no one else is going to do it for you.

The boldfaced is mine. This is the most important part. This is not just about writing.

From My Actual Life

I discovered Wordle last week while looking over a friend’s shoulder. I showed the word on Twitter.

Like a drunk orc hobbling out of its winter cave. Clueless.

Luckily, I nipped the ratio in the bud quickly by deleting the Tweet when others informed me of my spoiling ways (thanks Tina!).

I had avoided the game for a long time because I didn’t want to take drugs. But the one-word-a-day design is built-in chastity so I gave myself permission.

Its cryptography aspect reminded me of Mastermind (described in my older post Fun Ways To Teach Your Kids Encryption), but having it be a word game is a seductive mix of Scrabble + logic.

Meatspace Wordle

Use pen and paper to play Wordle with your kids. Take turns giving words vs solving the puzzle. You can do this anywhere and use the number of guesses as the basis for a scoring system.

For advanced players, consider a quadratic scoring system (ie make your score proportion to the inverse square of how many guesses it take…4 guesses is worth 1/16 of a point, 3 guesses is 1/9, 2 is 1/4 and so on). This might disincentivize the algorithmic approach and optimize for trying to guess the word earlier. I haven’t thought about it hard enough, but it would be an interesting problem to compute just how steep the scoring system’s decay function would need to be to justify the informed guess approach.

Stay groovy,

Kris

Thank you, and thanks for pointing out the typo. Grammarly failed me.

That's a fantastic post Kris! I've been guilty of looking for writing advice more often than I should. It's true that there are a lot of lessons that need to be internalized as opposed to being condensed into listicle format. But the advice to take what you do seriously, because not many other people will, that's precious.

Also, the observation that becoming a professional at anything involves mundaneness/pain, and picking the right field based on which pain you can tolerate the best, that's good advice. I'm still looking. :)

Note: it points to such an honset concern -> Typo